Urban drones: the facility location problem

Do cities need drones?

According to a report by the United States Federal Aviation Agency, 4.47 million small drones are expected to operate in the United States by 2021, up from today’s 2.75 million. Since 2017, more than 1 million drone owners have already registered with the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). So far, as expected, the main driving force behind this rapid increase in commercial drone purchases is their high mobility and applications in computer vision: taking pictures in dangerous areas, building inspection, traffic monitoring, photogammetry, etc.

However, this is just the beginning. Drones are expected to carry out important tasks in future cities: They will provide a bird’s eye view from the sky reporting in no time if a bridge is about to collapse, a fire is spreading or a human being is in trouble. They will supplement our transport systems by moving things around or getting someone somewhere quickly. In fact, Amazon’s Prime Air drone delivery service is already in its final development stage before beginning operations. Drones will also be robots on wings, performing such tasks as repairing bridges or fighting fires.

In this post, we will discuss how drones will affect cities, and how urban planners will have to extend their scope of expertise to be able to deal with urban airspace, urban air traffic, and its interplay with traditional urban space. We will do this by solving the problem of the efficient placement of drone stations in a city and seeing how different urban air traffic configurations lead to different operation zones and urban mobility.

Why should urban planners be concerned?

So far, most of us have seen drones only occasionally. But what will happen when swarms of drones flood our cities? We can confidently expect the deployment of drones at scale to pose some significant challenges to planning, managing, and designing sustainable cities. The proliferation of drone technology at scale would have an impact on the very nature of our cities. Certain types of drone applications will require new physical infrastructure.

Drone systems could affect the way buildings are designed and built. For instance, if drone docking stations will be placed on building roofs, the rooftop will have to be easily accessible for humans, but also for transporting goods to and from it. New buildings would have to be designed to accommodate this (for example, with additional internal or external elevator shafts). It could also be a serious challenge retrofitting old buildings to the new conditions. The visual impact on the built environment would also need to be addressed.

New types infrastructure such as passenger and logistic hubs forming a drone mobility network, as well as ground-based counter drone systems equipped with radars, signal jammers and drone capturing technology for combatting drones with rogue or dangerous behaviour will emerge. No-fly zones over critical infrastructure and buildings such as government buildings, airports or prisons will have to be designated and enforced via geo-fencing. Integrating all of this with the existing built environment and creating the necessary regulatory framework for it to function will have a great impact on the daily practice of architects, urban planners and policy makers.

Highly automated drone operations will require fixed docking stations for take off and landing, integrated with charging or refuelling systems. This could be a mobile or permanent station placed on the top of buildings, at street level, integrated into existing transport infrastructure or other types of infrastructure such as lampposts for smaller stations. These docking stations will most likely be integrated with electric battery charging. Given the energy policies of most developed countries, the impact of the soaring electricity demand on the grid and associated emissions will have to to be considered and carefully planned for.

For instance, the cost of privately owning drones can be considerably more expensive compared to renting them, especially for companies who may only require drones for a single task. However, with a city-wide rental system in place, the city, companies, and users will not be required to purchase drones, effectively distributing the cost amongst them. Therefore, planning a drone rental service based on a system of drone ports (or stations) distributed across the city is necessary. By providing a public drone rental service of distributed autonomous drones waiting at drone stations, this can reduce the total number of drones in the sky and the total cost of utilizing drones to complete tasks requested by the city services, citizens, and other users. This implies the necessity of addressing the following questions among many others:

- Where to place the docking stations?

- How many of them?

- With what capacity?

The facility location problem

The above questions can be answered with the help of mathematical optimization, particularly with linear programming if formulated as a capacitated facility location problem.

The latter is a classical optimization problem for choosing the sites for factories, warehouses, power stations, or other infrastructure. A typical facility location problem deals with determining the best among potentially available sites, subject to specific constraints requiring that demands at several locations be serviced by the opened facilities. The costs associated to such an initiative include a part which is usually proportional to the sum of distances from the facilities to the demand locations, as well as to the costs of opening and maintaining the facilities. The objective of the problem is to select facility sites in order to minimize total costs. The facilities may or may not have limited capacities for servicing, which classifies the problems into capacited and uncapacited variants.

Let’s give some context!

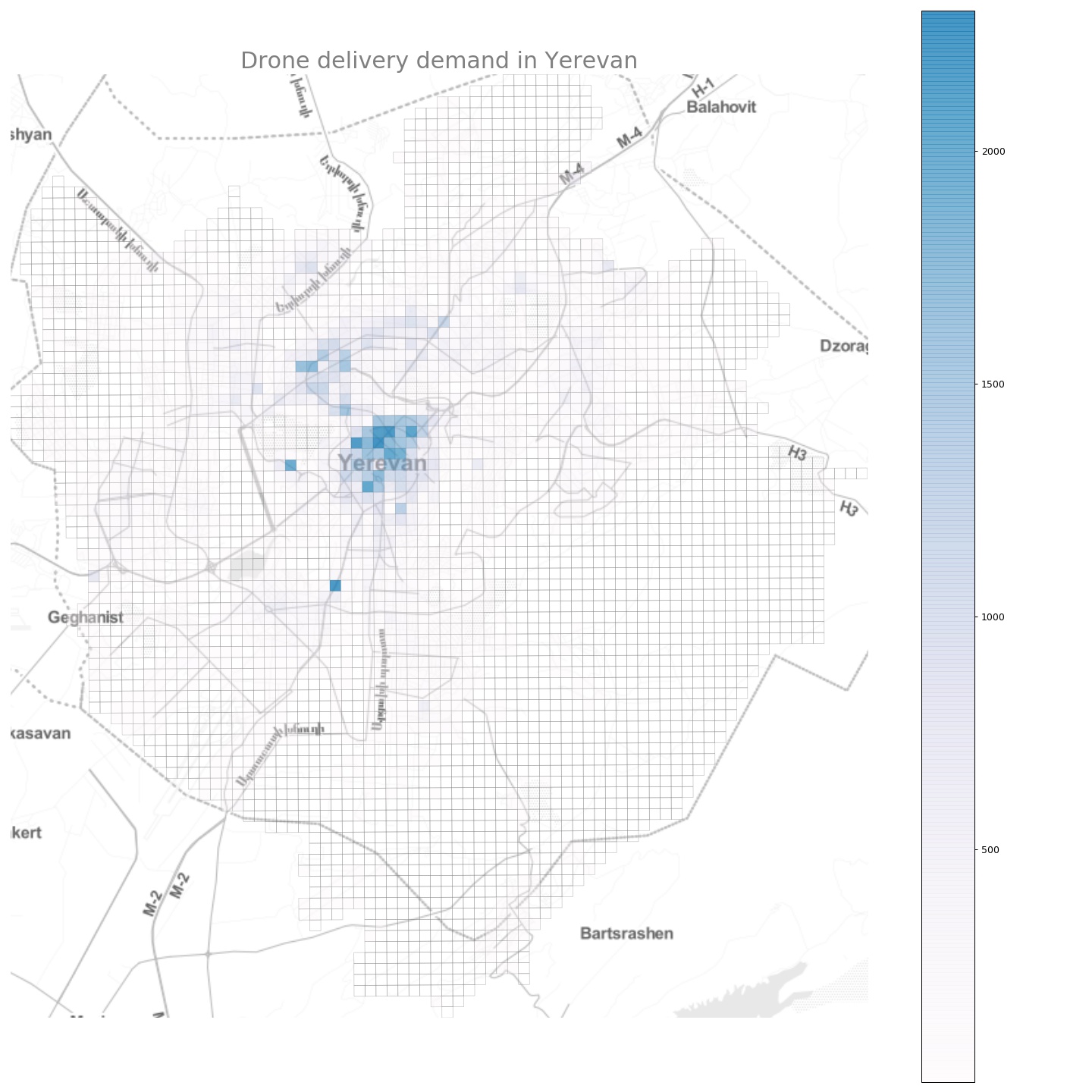

Imagine a situation in which we are tasked with sketching a concept plan for the placement of drone docking stations in Yerevan city. Having the spatial distribution of daily (hourly, weekly, or monthly for that matter) nominal demand in the city (for demonstration purposes taxi demand has been used as a proxy):

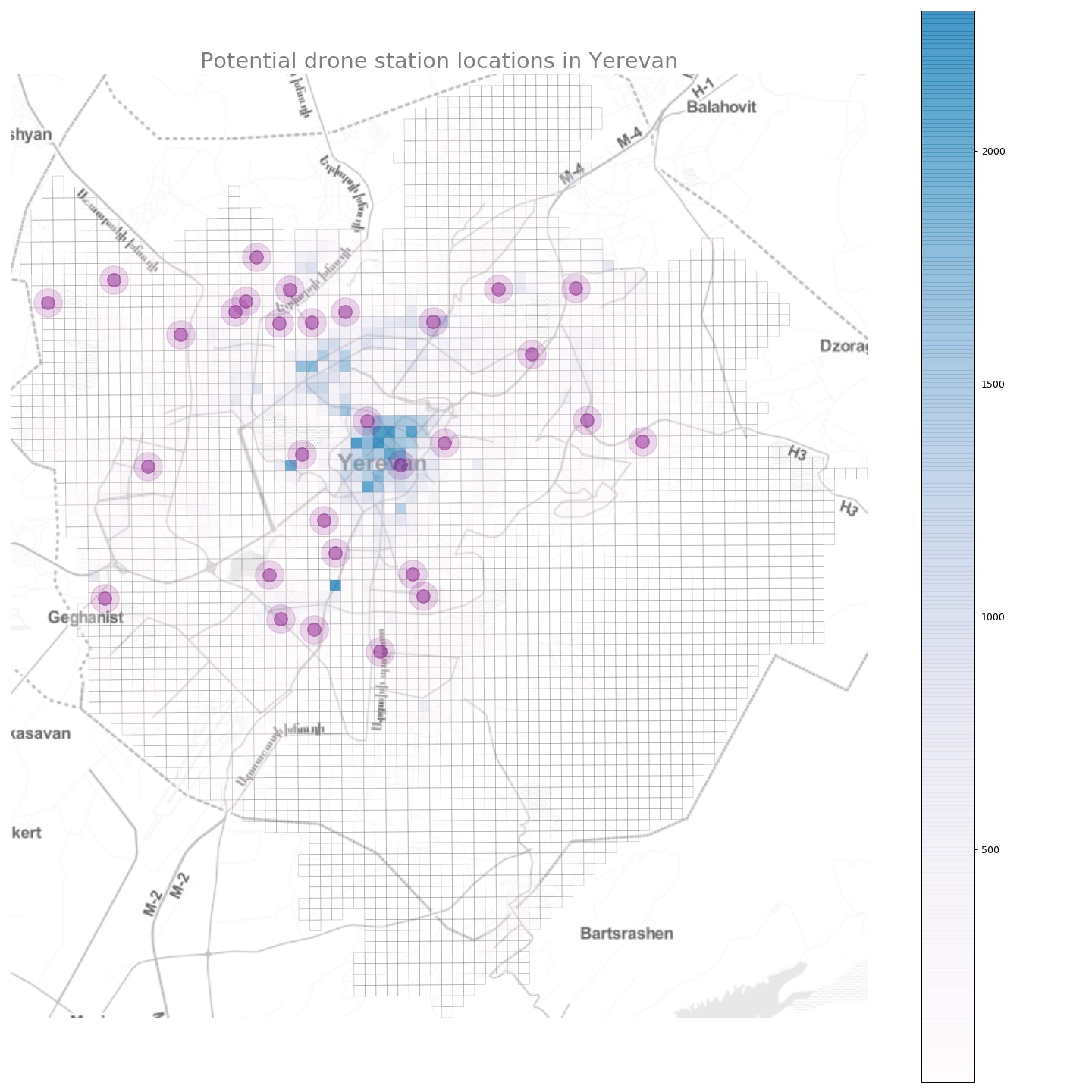

as well as a number of potential sites to install drone stations (30 in our example):

how do we determine the best locations for placing the docking stations? Well, it obviously depends on the costs.

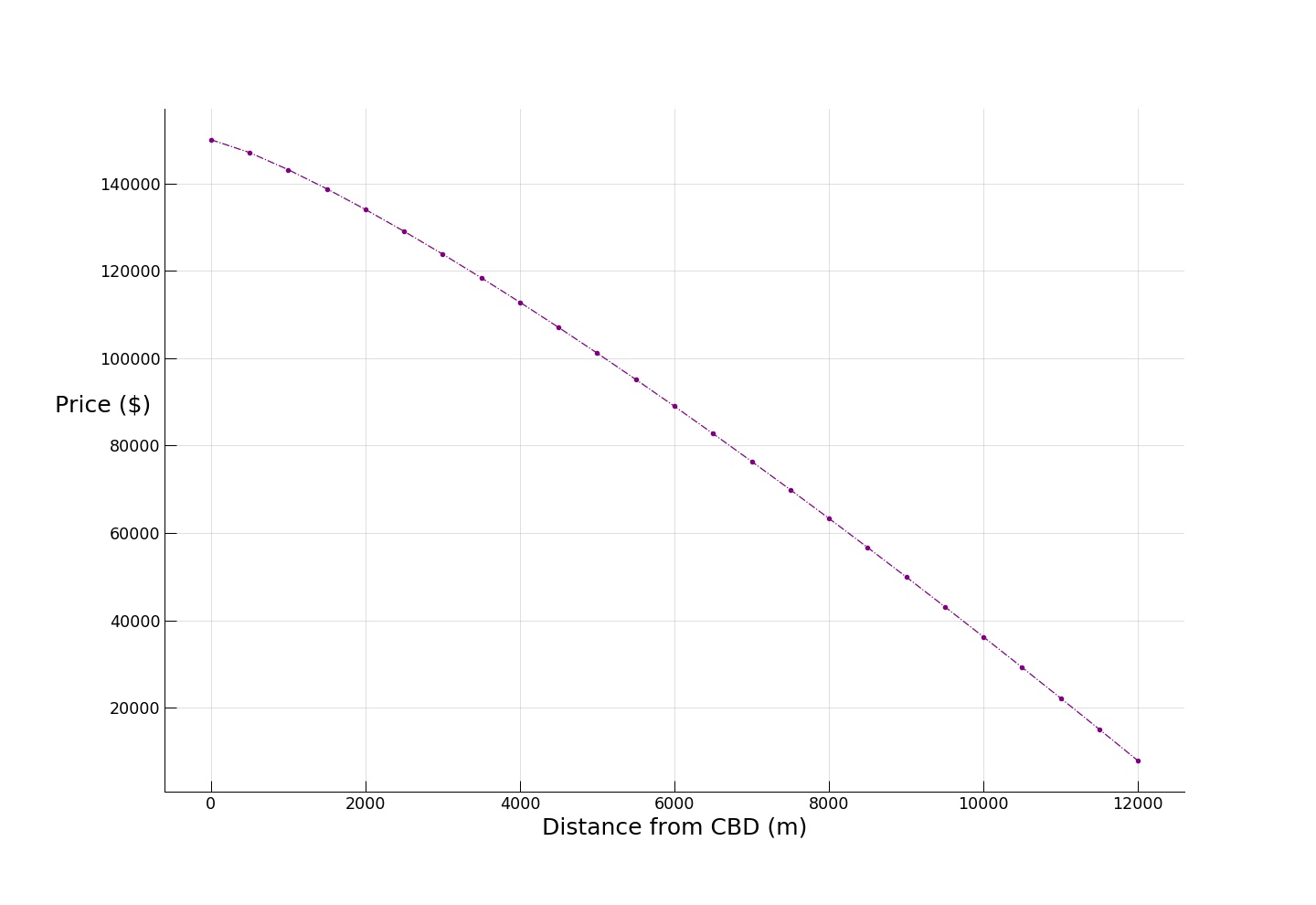

The first type of cost is that of purchasing and installing the docking stations. To simplify matters, let’s assume Alonso’s monocentric city model according to which real estate prices drop according to some exponential or power decay with increasing distance from the central business district:

There is clearly a tradeoff: while most demand is spatially concentrated in the center (see demand plot), and it would therefore make sense to also install docking stations in central locations to reduce transfer costs, we would, conversely, incur higher costs for choosing central locations (while prices have been chosen with some common sense, they are presented for demonstration purposes only).

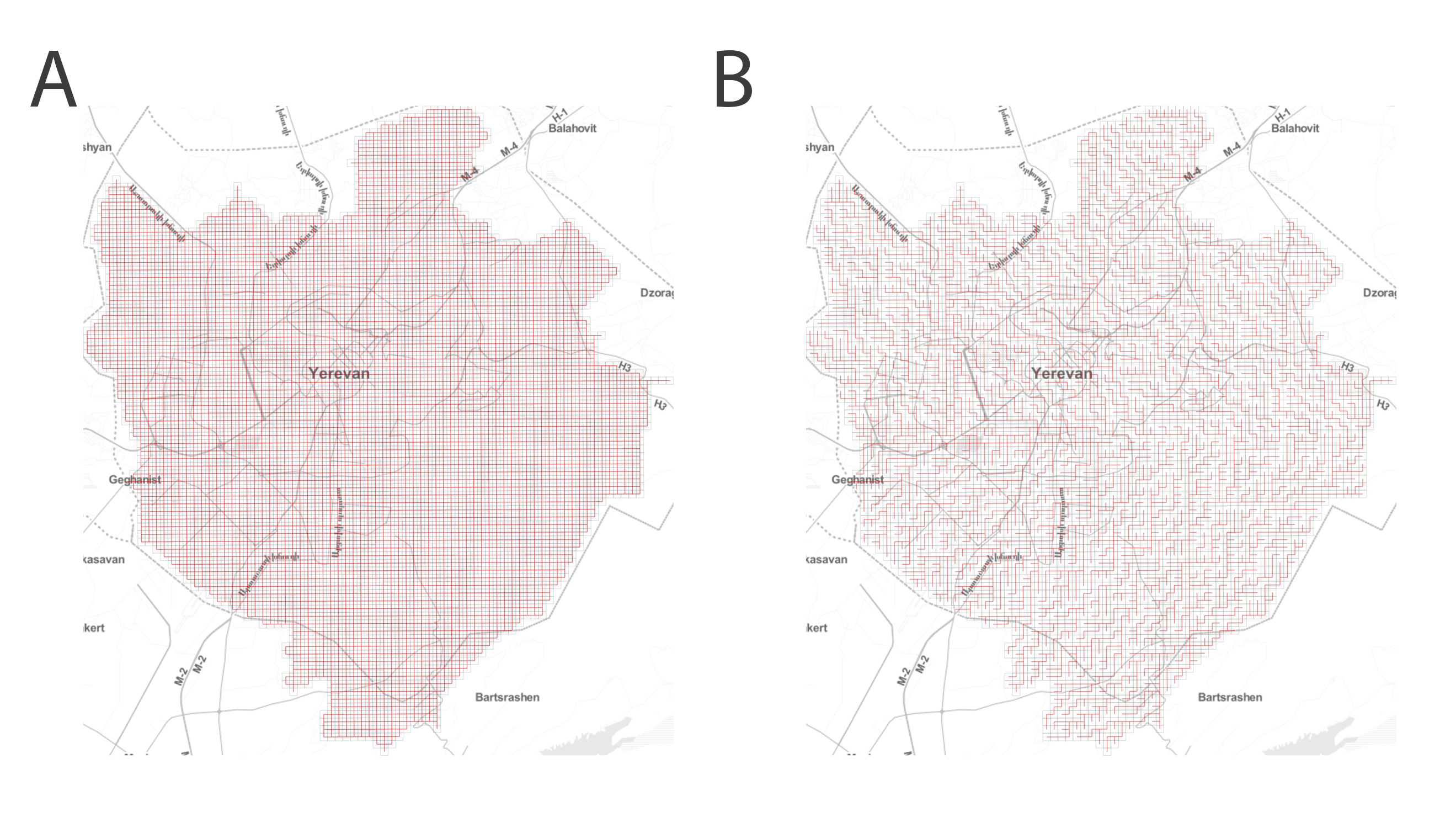

The second type of cost is that of operating the drones which can be safely assumed to be proportional to the distances travelled. However, and here things get interesting, these distances will depend on the underlying (actually upperlying) urban air traffic path ways! In the below image, we can see two examples of simple configurations for air traffic, a Cartesian grid (A) and a labyrinthine arrangement (B):

Let’s check out two more examples: a minimum spanning tree of the grid above, typically used in building the physical lines in communication networks for reducing the total line length (C), and the actual Yerevan street network, since one of the realistic scenarios is that drones will operate directly above the existing street network for reducing visual pollution and for safety reasons (D).

Since the four air traffic path way systems are so different, we can intuitively expect the solutions to the drone station location problem to yield differences as well.

Mathematical formulation

In order to see whether this is true, how the solutions compare, and what this means for future urban planners and traffic engineers, we need to solve a linear optimization problem. Consider \(n\) customers \(i=1,2,...,n\) and \(m\) sites for placing the drone docking stations \(j=1,2,...,m\). Define continuous variables \(x_{ij} \geq 0\) as the amount serviced from drone station \(j\) to customer \(i\), and binary variables \(y_j=1\) if a drone station is installed at location \(j\), and \(y_j=0\) otherwise. An integer-optimization model for the capacitated facility location problem can now be formulated as follows:

\[\begin{array}{ll} {\text { minimize }} & {\sum_{j=1}^{m} f_{j} y_{j}+\sum_{i=1}^{n} \sum_{j=1}^{m} c_{i j} x_{i j}} \\ {\text { subject to: }} & {\sum_{j=1}^{m} x_{i j}=d_{i}} \\ {} & {\sum_{i=1}^{n} x_{i j}=d_{i}} & {\text { for } i=1, \cdots, n} \\ {} & {\sum_{i=1}^{n} x_{i j} \leq M_{j} y_{j}} & {\text { for } j=1, \cdots, m} \\ {} & {x_{i j} \geq 0} & {\text { for } i=1, \cdots, n; j=1, \cdots, m} \\ {} & {y_{j} \in\{0,1\}} & {\text { for } j=1, \cdots, m} \end{array}\]The objective of the problem is to minimize the sum of drone station installation costs and drone operation costs. The first set of constraints require each customer’s demand to be strictly satisfied. The capacity of each drone station \(j\) is limited by the second set of constraints: if drone station \(j\) is installed, its capacity restriction is taken into account; if it is not installed, the demand satisfied by \(j\) is zero. The third set of constraints impose variable upper bounds. Even though they are redundant, they yield a much tighter linear programming relaxation than the equivalent weaker formulation (a very good introduction to linear programming can be found here). For an intuition of how such problems are solved, this Wikipedia article provides a fairly good first overview. Fortunately, there are many good mathematical optimization solvers out there. Let’s see how to code it ourselves:

Python code for solving the capacitated facility location problem

from pulp import *

COSTUMERS = positive_flow_inds # the demand vector

potential_stations = np.random.choice(COSTUMERS,30) #choose 30 potential sites

STATION = ['STATION {}'.format(x) for x in potential_stations]

demand = dict(polyflows[polyflows.inflow>0]['inflow']) #setting up the demand dictionary

STATION_dict = dict(zip(STATION, potential_stations))

#installation cost decay from center (given a vector of distances from a central location)

costs_from_cen = 150000 - 1.5*dists_from_cen**1.22

install_cost = {key: costs_from_cen[val] for key, val in STATION_dict.items()} #installation costs

max_capacity = {key: 100000 for key in FACILITY} #maximum capacity

#setting up the transportation costs given a distance cost matrix (computed as pairwise shortest paths in the underlying air

#traffic network)

transp = {}

for loc in potential_stations:

cost_dict = dict(zip(COSTUMERS, costmat_full[loc][COSTUMERS]))

transp['STATION {}'.format(loc)] = cost_dict

# SET PROBLEM VARIABLE

prob = LpProblem("STATIONLocation", LpMinimize)

# DECISION VARIABLES

serv_vars = LpVariable.dicts("Service",

[

(i,j) for i in COSTUMERS for j in STATION

], 0)

use_vars = LpVariable.dicts("Uselocation", STATION, 0,1, LpBinary)

# OBJECTIVE FUNCTION

prob += lpSum(actcost[j]*use_vars[j] for j in STATION) + lpSum(transp[j][i]*serv_vars[(i,j)]

for j in STATION for i in COSTUMERS)

# CONSTRAINTS

for i in COSTUMERS:

prob += lpSum(serv_vars[(i,j)] for j in STATION) == demand[i] #CONSTRAINT 1

for j in STATION:

prob += lpSum(serv_vars[(i,j)] for i in COSTUMERS) <= maxam[j]*use_vars[j]

for i in COSTUMERS:

for j in STATION:

prob += serv_vars[(i,j)] <= demand[i]*use_vars[j]

# SOLUTION

prob.solve()

print("Status: ", LpStatus[prob.status])

# PRINT DECISION VARIABLES

TOL = .0001 #tolerance for identifying which locations the algorithm has chosen

for i in STATION:

if use_vars[i].varValue > TOL:

print("Establish drone station at site ", i)

for v in prob.variables():

print(v.name, " = ", v.varValue)

# PRINT OPTIMAL SOLUTION

print("The total cost of installing and operating drones = ", value(prob.objective))

The four solutions

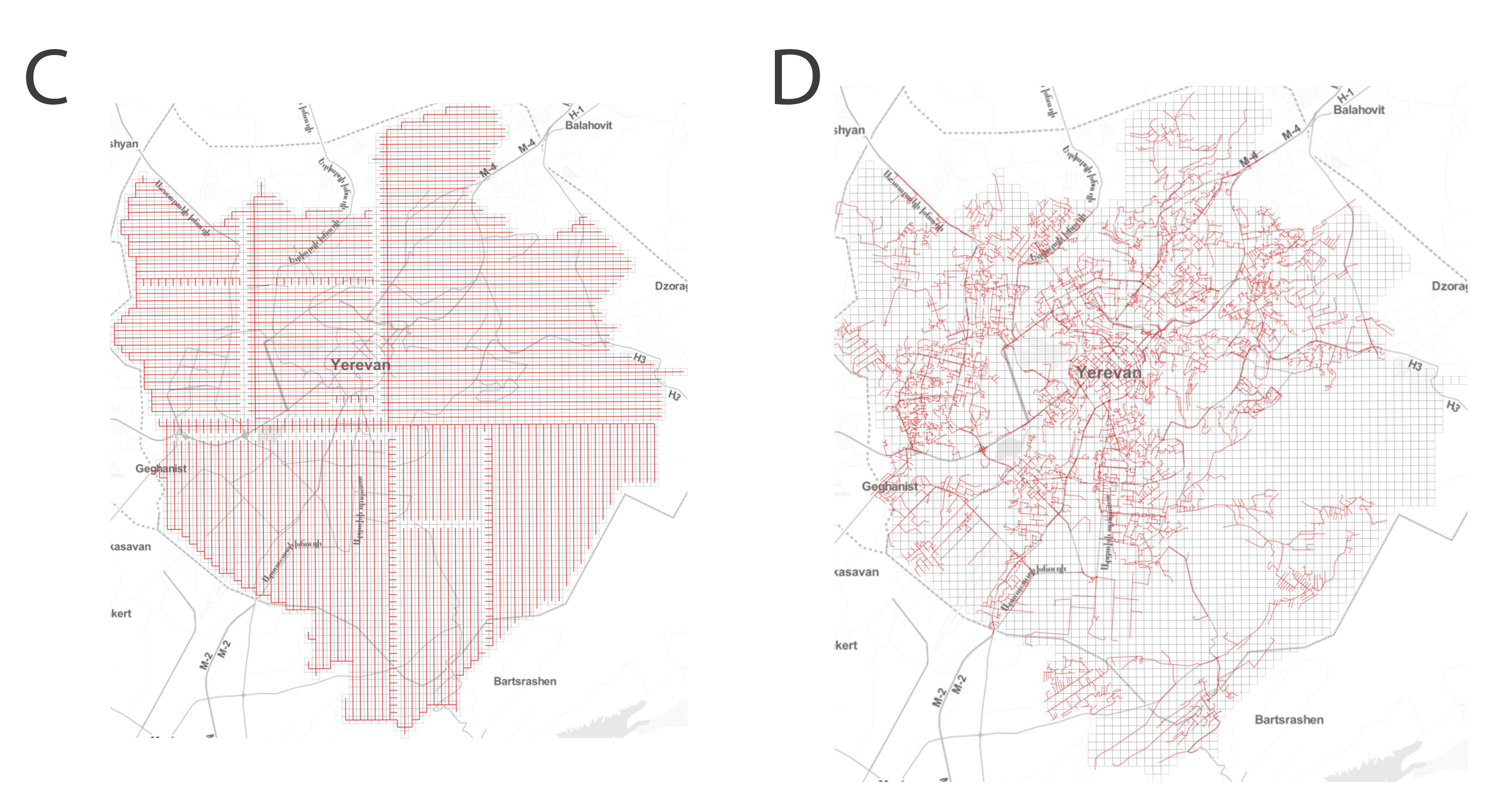

Solving the optimization problem above yields the following solutions for configurations A and B:

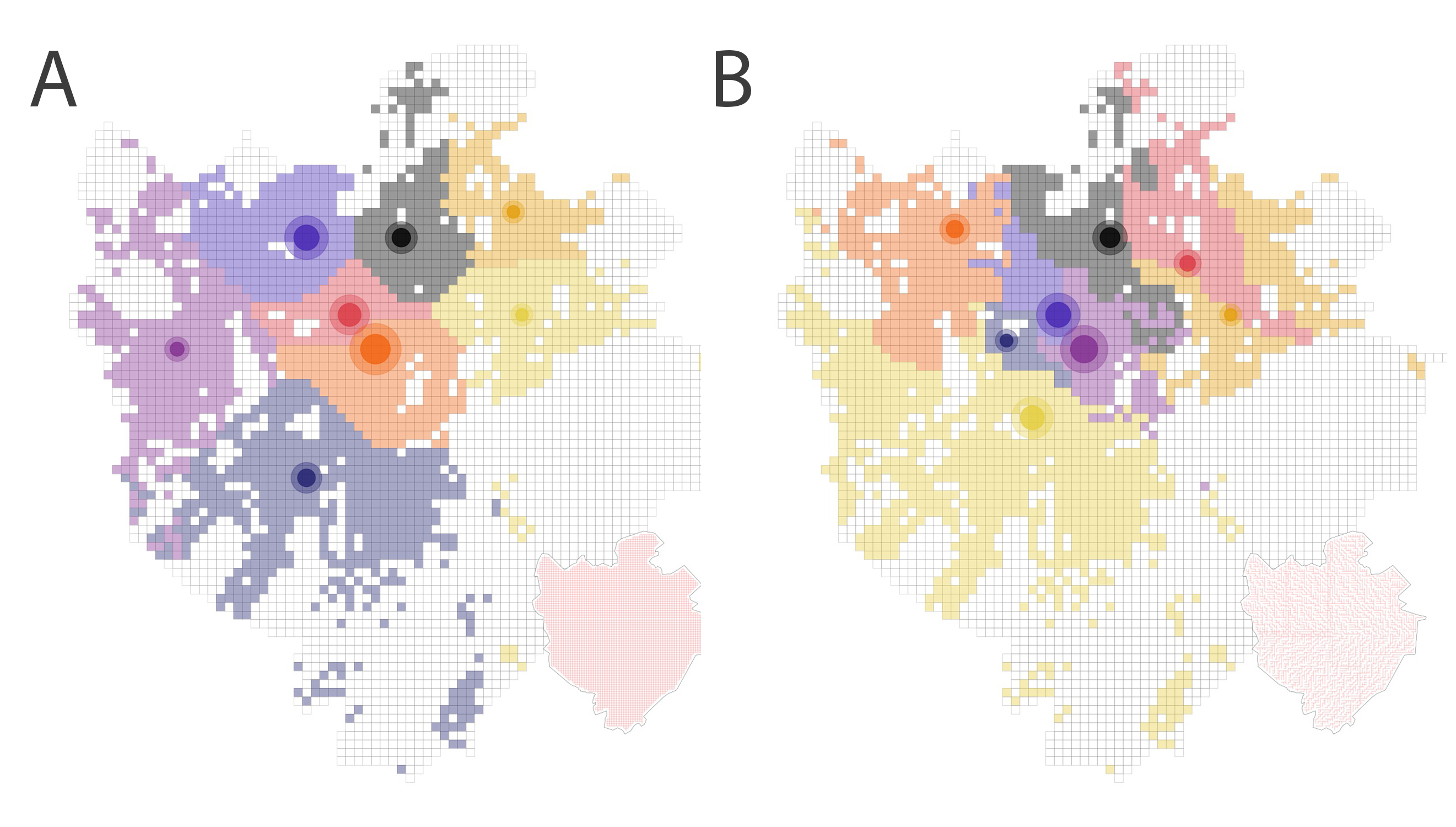

and for C and D:

A small animation for the exisiting street network configuration to illustrate the system dynamics:

We see from the plots that while there is a common optimization pattern across all four arrangements with roughly similar optimal numbers of drone stations (from 8 to 11) and similar spatial clustering of large supplier stations (larger circles denote larger supply), the optimal locations and demand coverage areas (shown in colors) vary a lot!

This means that small variations in air traffic path way designs can have a huge impact on the optimal locations of drone stations, the geographical area covered by each station, and the volume of air traffic in different areas. We can also look at the optimal total cost for each air path way system. In particular, we find that the best path way system is the Cartesian grid (~2.5 million $), then the existing street network (~4.1 million $), then the labyrinthine system (~4.5 million $) and the worst is its minimum spanning tree (~6 million $). We see that the results hint at the tradeoffs future planners will have to face: cost vs. safety vs. aesthetics vs. practicality.

Conclusion

In this post, we attempted to raise awareness and alert architects, urban planners, and policy makers to the dramatic changes unmanned aerial vehicle technology is about to bring to our cities. We looked at the case of Yerevan and solved a simple mathematical optimization problem for finding the best locations for drone docking stations to serve the demand (both commercial as well as city operations such as emergency services). We saw how differences in planning the urban air space could have a large impact on the solution of the aforementioned problem. Unlike the urban street space, which, for the most part of its existence has evolved gradually, the urban air space will have to be planned, designed and deployed in comparably miniscule time frames.

There will obviously be many more variables to consider when solving the facility location problem in a real setting making optimization problems much harder to solve. For instance, in our example we assumed a one-off demand structure, while in most real-world settings the demand is volatile calling for stochastic optimization.

However, the objective of this post was not to provide a manual for solving the drone station location problem (let’s leave it to operations research professionals), but to show its impact on urban space and mobility, and to point at the necessity to extend urban planners’ and other city enthusiasts’ scope of interest.